Nigerians are counting on 37 judicial panels to get redress for being abused and brutalised by their police. But here is how a failed internal system of discipline makes the cops ever brutal.

By Funke Busari

The dead can’t celebrate victory. Otherwise late Kudirat Abayomi should be thumping the air with her fist by now for getting the desired redress over the brutal manner she was murdered in April 2017. A stray bullet from a policeman now on the run sealed the fatal deal.

So the late bean-cake seller will never spend the N10 million compensation served her on Friday, 19th February, 2021 by the Lagos State Judicial Panel of Restitution and Inquiry set up to investigate cases of police brutality especially involving officers of the now-defunct Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS).

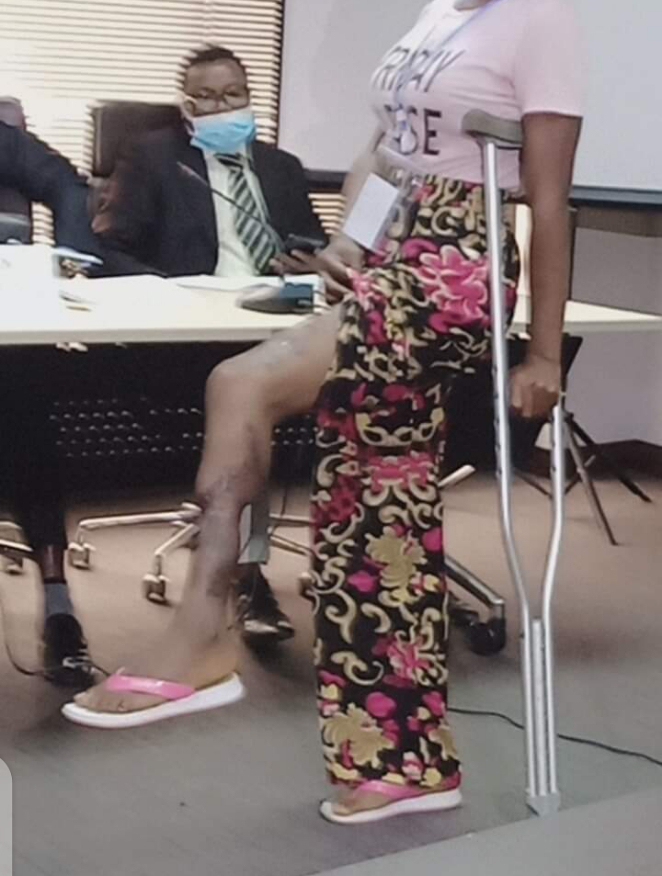

Hannah Olugbode, 35-year-old hairdresser, would not be dancing away her mental torture either. She now depends permanently on crutches to navigate the streets after a stray bullet fired by some SARS operatives around the Ijeshatedo area of Lagos shattered her legs.

In the case of Hannah, the judgement noted particularly that all was not totally well with the hairdresser. She has to undergo treatment, sustain and keep her body. And the compensation should help with the stress and anxiety she suffered, Retired Justice Doris Okuwobi ruled.

The Nigerian police complaint apparatus remained on the fritz for years until emergency judicial enquiries became necessary to dispense justice to victims of police brutality, despite thousands of their complaints earlier.

But after six months, the on-going enquiries will grind to a stop. And, in all likelihood, the complaint channel will continue as usual, clogged with years of unresolved complaints and anger, until its pressure valve bursts again, as it did in October. Violence and frustration will then erupt, and another nationwide enquiry begins for retribution.

It’s a cycle Nigerians have seen, at least six times since 1999. And that seems how the Police Service Commission have primed the police disciplinary machinery to run.

As at the end of December 2020, eight weeks after the climax of the anti-police brutality protest on October 20, no fewer than 2,570 petitions were filed by Nigerians who have been victims of police brutality in 30 states and FCT according to a report.

Lagos has more than 230 of the petitions; Abuja, over 245, though mostly about the clampdown on the protest. Rivers had 181.

But, so far, only 37 cops of the disbanded police squad have been officially handed over for prosecution, after the National Human Rights Commission-led judicial panel investigated a report President Muhammadu Buhari requested on the violence of the squad.

The state governments say the judicial panel’s wheels grind slowly. That’s understandable. And the court process, following the panels’ recommendations, is also going to take time.

All the slow pace and delay, however, are not new.

CaseFile’s analysed complaints—of professional misconduct, excessive use of force, obtaining money for police bail, benefit, incivility, and others—the police documented since 2016. It turns out there is nothing earnest in how the police handles complaints against its officers and men. The newspaper also found out the punishment or discipline the police applies to the highest category of the complaints, professional misconduct, is mostly hyped in the media, to project an image of a disciplined force.

Sometime in 2017, for instance, officers Okelue Nkemeonye, Braimoh Sunday and Yusuf Olukoga impersonated SARS in the Ikorodu Area of Lagos. They rounded up three men, and branded them Yahoo Boys. The three suspects eventually coughed up N200,000 paid into a third-party account before they were released.

The complaint was investigated, and the three cops were dismissed. According to a statement by Assistant Commissioner of Police and then-Head, Police Complaint Rapid Response Unit (PCRRU now CRU) Abayomi Shogunle, then-IGP Ibrahim Idris was happy the citizens complained.

“The IGP has also said that all allegations of professional misconduct reported against any police officer would be treated in line with relevant laws and in keeping to the ‘Change Begins With Me Campaign’ of the federal government,” said Shogunle.

The excitement that greeted the announcement was palpable in the Ikorodu case—just as it has been, especially in most of the police disciplinary action against professional misconducts.

But at Awkuzu, in Anambra, the discipline didn’t come fast. In fact, it never came, despite a deluge of complaints from relatives of mortally brutalised citizens, NGOs, lawyers, and others against then SARS commander, James Nwafor.

As figures of complaints before the state’s judicial panel now reveal, Anambra has no fewer than 144 petitions. Of the cases heard so far, Nwafor has appeared in over 90 percent.

In spite of his wide-ranging atrocities, Nwafor retired in 2018, got away with the allegations of brutality and killing. He even bagged an appointment as a security adviser to Gov. Willie Obiano, before the October incident began to haunt him.

Nwafor’s would be among the 5,341 complaints the Police Complaint Rapid Response Unit documented in snatches of files in 2016, 2017 (Q1 and Q3), 2018 (1st half) and 2019 (annual) reports.

Of these, complaints of professional misconduct, excessive use of force, and obtaining money for police bail, in that order, have been dominant over the years. And the highest number of complaints always come from Lagos, followed by Abuja, and Rivers, in that order.

For the four years, Lagos had 1,082, Abuja, 661, and Rivers, 649. Across the three states, professional misconducts took the highest figures—1,383; followed by obtaining money for bail—606; and excessive use of force—403.

Lagos led in the professional misconduct category with 543, and 193 in excessive use of force, ahead of Abuja’s 465 and 117 respectively in those two categories. Rivers only led the pack with 281, followed by Lagos 246 when the complaints were about money for bail. It had 275 in professional misconduct. Police taking money for bail seems less rampant in Abuja.

These three states, with a total of 2,392 complaints in those three areas, incidentally became the hotspots of the October EndSARS protest and consequent violence.

Elsewhere, the most reported of police lawlessness remains the excessive use of force. The consequences of that brutality have always been extra-judicial killings and bodily injuries to citizens. But not much disciplinary action the police takes against its indicted officers for use of force hits the headlines. Unlike professional misconduct whose sanctions are the most publicised.

In a sense, professional misconduct, use of force, taking money for bail, benefit, and incivility overlap somehow in the CRU reporting. The grey area becomes even more glaring when comparing what the victims state, and what the police usually proclaims when it dare hammer its erring officers.

Such blurring happened in September 2020. The PSC approved the dismissal of 10 officers for certain acts, according to Musiliu Smith, chairman of the commission.

“The dismissed ACP, Magaji Ado Doko, was found to have engaged in acts unbecoming of a public Officer,” PSC media head Ikechukwu Ani said.

What about the acts: disobedience to lawful order; discreditable conduct; unlawful use of authority and scandalous conduct.

Ani also said one of the dismissed SPs, Ogedengbe Abraham, was found guilty of negligence/loss of government property; disobedience to lawful order and act unbecoming of a public officer. “The other dismissed SP, Mallam Gajere Taluwai, was found guilty of discreditable conduct and act unbecoming of a Public Officer,” he added.

Whatever all these mean to the police, there’s no statement of offence in concrete terms the complainants of brutality can grasp.

Ani and Shogunle might be exaggerating the picture, for good public relations when it comes to how much police authorities frown on what they call unprofessional conducts. Drilling through the puffery, one could have expected the police rule book to delineate the categories. They, however, remain foggy.

According to the Guidelines for Discipline (Minor Offences) in the NPF which the PSC first published in 2006, misconducts can be major or minor.

“A minor offence or misconduct shall include any act, omission or commission or wrongdoing, the prescribed punishment of which does not, in any case of conviction in criminal proceedings, exceed a term of imprisonment for six months,” Section 6 of the guideline states.

Among such wrongdoings are: driving police vehicles when not properly dressed, riding on tailboard, improper dressing, lateness, malingering, sleeping on duty, smoking, drinking on duty, and others.

The Police Act 2020, Section VII, also states how police officers must not injure citizens or destroy public properties, lend or borrow money, and so on.

But the problem is: Violation of these codes, no matter its sanction, pales into insignificance when they are compared with police brutal and lethal use of force, and the contravention of the Police Order 37 that specifically spells out use of firearms or lethal force, which, in itself, is not an issue. Except for abuse. (And there is plenty of that)

The Order’s section (a) states: When attacked and there is an imminent threat that the police officer will be killed or seriously injured, and no other means are available to avert or eliminate the danger of saving his/her life. In such circumstance, a Police Officer would have to prove that he was in danger of losing his life or of receiving an injury likely seriously to endanger his life. It would be most difficult to justify the use of firearms if attacked by an unarmed man. If persons made a concentrated attack upon him, armed with machetes, firearms or bow and arrow or other lethal weapons he would be justified in using a firearm to save his life. In a case where a person fires at him, he would also be justified in firing to defend himself. If attacked by an individual with a heavy stick or machete he would have to prove that other less lethal means available to him were not sufficient to protect his life

No fewer than 35 police officers ran afoul of the order in Lagos between 2016 and 2020, resulting in 21 deaths, going by public records. There might be other incidents, but not officially reported and documented. All the same, the state police command and the PSC ensured they made a show of their efforts on those occasions they publicly dismissed more than two dozen cops involved in 11 of the incidents.

To be sure, Lagos recorded 193 public complaints of brutality between 2016 and 2019, according to the CRU. But only 24 incidents could be traced within the period. No doubt some of the complaints could have been dismissed as untrue. But the difference, less than 169, is still very high. That indicates many complaints of excessive use of force were swept under the carpet. At least 13 cases were not declared by the police, according to records by the state justice ministry.

From media records, the command declared only 11 cases—mostly incidents that happened between 2019 and 2020. Two of them were filed in court; the defendant in one, Daniel Ojo, who shot one Akomalufe in the head, and killed his girlfriend right there, in 2019, escaped; seven are yet to be filed; and one, the state government record revealed, was just filed in court.

The government record was made open after the October 20 incident at the Lekki Toll Gate. The state’s ministry of justice rolled out 31 names of cops who are defendants in a 20-case prosecution list.

It was another show, Governor Babajide Sanwo-Olu said, of commitment to end police brutality in the state. But three of those 20 cases he flaunted were recorded between well before 2016, and more than five years later, they are still in court. One of the cops, Aremu Musliu, 28 then, shot Godwin Ekpo, a tricycle rider, and his wife dead in 2015.

Again, four of the cases Lagos made public were among those the state police command couldn’t declare as dismissed. Those defendants include officers Aminu Joseph and Pepple Boma who allegedly committed murder and manslaughter respectively. Though in court, their trials and two others have yet to commence.

Seven other incidents the Lagos police command was silent on were already in court, and their trials, in full swing. The suspects: Officers Adebayo Abdullah, Mohammed A. and two others, Matthew Ohansi, Adamu Dare, Mark Argo and five others, Emmanuel Uyankweke, and Edoke Okhide—had their last adjournment in September and November. All of them were charged with murder, attempted murder, and manslaughter. Two others—separate murder cases involving Officers Afolabi Saka and Monday Gabriel—were just being filed in court, the government record revealed. Neither the police nor the state is ready to reveal more particulars of the cases.

With all its show of discipline and zero tolerance for police brutality, the Lagos police command can only point at three cases it made public, and duly handed over for prosecution: Officer Ogunyemi Olalekan whose stray bullet killed a 36-year-old Kolade Johnson in the Mangoro area, Agege, in 2019; Officer Akanbi Lukmon who shot dead a partygoer he had an argument with somewhere on the Victoria Island in December 2019; the third was Ojo who shot a couple, killing one. He’s been on the run since then.

Apart from those police officers on the list of prosecution by the state, there is a number of cases the police have spoken about or captured in their exhibition of commitment to ending police brutality. But none of them has been prosecuted, going by the state’s list.

CASEFILE found seven of such. And the incidents of the brutality in those cases could be very touching. For instance, Justina, a 17-year-old, was hit by a stray bullet in front of her compound at Oworonshoki in May, 2020. She died. The two cops responsible for her death—Oguntola Olamigoke and Theophilus Otobo—were dismissed from the police by CP Hakeem Odumosu. Nothing else has happened since then. At least they are missing in the 20-case list the state released in October.

Others are: Inspector Charles Okoro who shot a 26 year-old cleric at Agege; Edwin Apalowo Ola and others, shot a club goer at Oshodi December 2019; Matthew Oche pushed a motorist into a drain at Iddo in 2016; Segun Okun and others shot a Lagosian in 2018; Fabiyi Omomayara, Ola Solomon, Solomon Sunday, Corp Aliyu Mukaila who shot two unarmed robbers at Igando in 2019; and Sgt. Idom in 2016.

All of their nine victims died.

Why these killer cops and others were indicted by the police as far back as 2016, but are yet to be sued, is a difficult question.

The police complaint system has its own loopholes. The CRU reporting has stuck up here as one of the weak points. And the disciplinary process just makes it worse.

By its own Act, the PSC investigates complaints, and takes action. The Act establishing the PSC (PSC Act 2001) empowers the commission to appoint into all offices except the IGP’s; to dismiss and exercise disciplinary measures over all except the IGP. The commission can also formulate policies and guidelines for discipline and dismissal of officers.

Clearly, the responsibility of discipline and dismissal of indicted cops lies with the PSC. But the Commissioners of Police, following the Police Act, too, initiate orderly room investigation and trials whose recommendations go to the PSC. This has been the major chain of command in police discipline. Which means the PSC carries out no independent investigation in dismissing bad cops in Nigeria.

On this and other issues about his unit, ACP Markus Ishaku Bashiran, whom former IGP Mohammed Adamu appointed to head the CRU last year, didn’t respond to questions asked through his Twitter account.

Citizens now worry about how recommendations from the 36 states of the federation and the FCT can be examined and implemented by the commission without delaying prosecution—or letting an investigation slip into oblivion.

That could explain why justice takes too long to serve in many complaints. The record Lagos published in October included at least three cases that predate 2016. Inspector Surulere Irede and two others were in court before Justice Sedotan Ogunsanya on November 13, their last adjournment. They were charged with manslaughter for a 2014 incident at Agege where they showered bullets on protesters throwing rocks at them. The police killed one of the protesting youth. Their arraignment came two years later—in 2016. They are still facing trial as of November 2020. Another cop, Musliu, who murdered a couple in a tricycle in 2015 has not been arraigned yet. Yet another one, Sgt. Gbanwuan Isaac, overused force, leading to his fiancé’s bodily injuries in 2012. He hasn’t been arraigned up till now.

With such reliance on what the CRU and police commands investigate and recommend before it can act, the PSC won’t be able to whack or kick out the bad ones in the police as expected: in all fairness and in good time.

It is then natural that backlogs of complaints and grievances unattended will mount over time. Such public frustration explodes into protests and violence at any slight opportunity.

Then when the balloon goes up like it did during the EndSARS protest, it serves little purpose setting up panels of enquiries as damage-control measures. Especially after the CRU and the PSC have failed in ensuring justice as police brutalises Nigerians. Panel recommendations, judicial or otherwise, on Nigeria’s police reforms have never been implemented—from the Dan Mandami Committee, and the M.D. Yusuf panel and the Uwais Electoral Reform Panel to the Parry Osayande’s and the 2019 Committee on SARS and two others. So the highest the current panel could go, many have projected, is to recommend discipline for the few bad cops, and compensation for their victims.

That works to calm frayed nerves just for a while.

But the channel of dealing with public complaints of police rights abuse, and the workings of the PSC remain as they have always been: only capable of penning up public angst and delaying justice by giving little attention to cops’ brutal use of force.